Oscar Nomination:

Documentary Feature

Documentaries are particularly difficult to review. The problem is that there are two very different subjects to think about in this kind of film – the subject of the documentary and the film itself. It is possible to have two entirely different reactions to those subjects. For example in RBG, a documentary about Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the 2019 Oscar list, I had completely positive sympathies for Ginsburg herself and admire her for a whole bunch of reasons, but felt the film came up short. I thought it relied too much on the ‘talking head’ notion, consisting almost entirely of testimonial interviews. It also seemed to idolize its subject, elevating her to almost mythical proportions which, I thought, demeaned the subject by not humanizing her. As a result, even though I loved the subject, I did not particularly care for the film. It is equally possible to have a subject that you find repulsive in a well-constructed film, as was evident in Fathers and Sons, about how terrorism sentiments are passed down from generation to generation in Palestinian Israel.

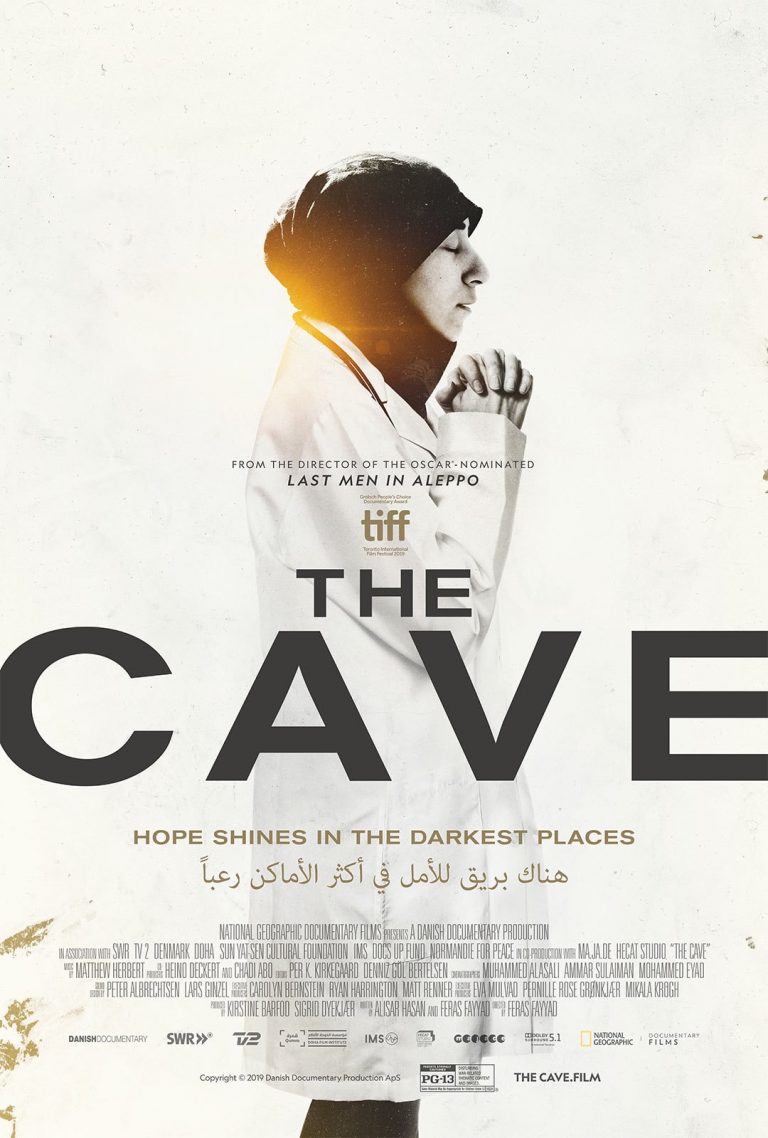

The Cave is the name of an underground hospital in Ghouta, a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Damascus. Syrias dictator Assad, with the aid of Russia’s dictator Putin’s warplanes, bombed his own citizens in an attempt to brutally suppress a civil war spawned by his own ruthlessness. In response, most of the inhabitants left the town to join rebel forces or even just more peaceful environments further North. Those that remained were either trying to retain a feeble hold on their lives or were fighting the Syrian army. Casualties were constant and hospitals, initially, were one of the few places that weren’t marked as targets. Increasingly, though, Assad’s forces targeted even those humanitarian outposts and the response was to build an elaborate underground system of rooms and tunnels called The Cave.

So, from the beginning, the subject of this documentary is of interest and sympathy – few rational and feeling people can’t help but have supportive feelings for Assad’s victims. To further amp up the interest and sympathy factor, the hospital is managed by a woman, Amani Ballour. Probably somewhere around 30, she paints an almost Mother Theresa image as a caring and effective person whose only true intent in life is to help her fellow Syrians and to save their lives when she can. Her mission is thwarted by her gender, however, as Syrian Muslim men are, generally, not sympathetic to a woman in a position of power and much less so in a war-time environment.

The documentary follows Ballour over the course of several days as she attempts to keep the hospital running even through intensive bombing of her neighborhood and, at one point, the hospital building itself. In the final scenes, Assad has deployed chemical weapons against his own people and Ballour’s team tries to desperately save children from the ravages of chlorine gas. We see her not only helping her medical staff treat patients, but also making popcorn as a feast for her team, short on food supplies but long on hope.

Ballour is a moving character. And the key strength of the movie is how it portrays the possibilities of hope and humanity even amid the tragedy of the Syrian disaster. You leave the movie with a curious mix of positive and negative feelings – disgust at the cruel behavior of their government, but admiration and even love for the people who desperately tried to fight it. The juxtaposition of emotions is a strength of the film.

It accomplishes it through very good film craft. Although the cinematographers are all freshly minted, they did a commendable job following Ballour and capturing the stark images of war and the underground hospital. The musical score did a terrific job of establishing the moods and setting the viewer expectations. And, as to be expected from a National Geographic film, the editing was tight and crisp.

Still, I can understand why the film didn’t win the Documentary Oscar. Brought to us by director Feras Fayyad, he also gave us The Last Men in Aleppo, a 1917 film about men fighting the Syrian regime in Aleppo – a different town with a similar subject. And the next film on our list, For Sama, is also about Syria. In short, the subject matter is getting overplayed. The tragedy of Assad’s inhumanity is still, of course, reprehensible and he deserves the firing squad. But as the subject matter for documentary films, the subject is getting too much airtime. Perhaps we need to be reminded of the problem from time to time, but it isn’t us who needs to be motivated into action – it is our world leaders who control the levers that reward these miserable dictators. Maybe they should be required to watch all of these films over the course of a single day.

But the point is, this isn’t Oscar winning material anymore – I feel like I’m getting beaten over the head. For a good film, but not a necessary one (3 Stars).