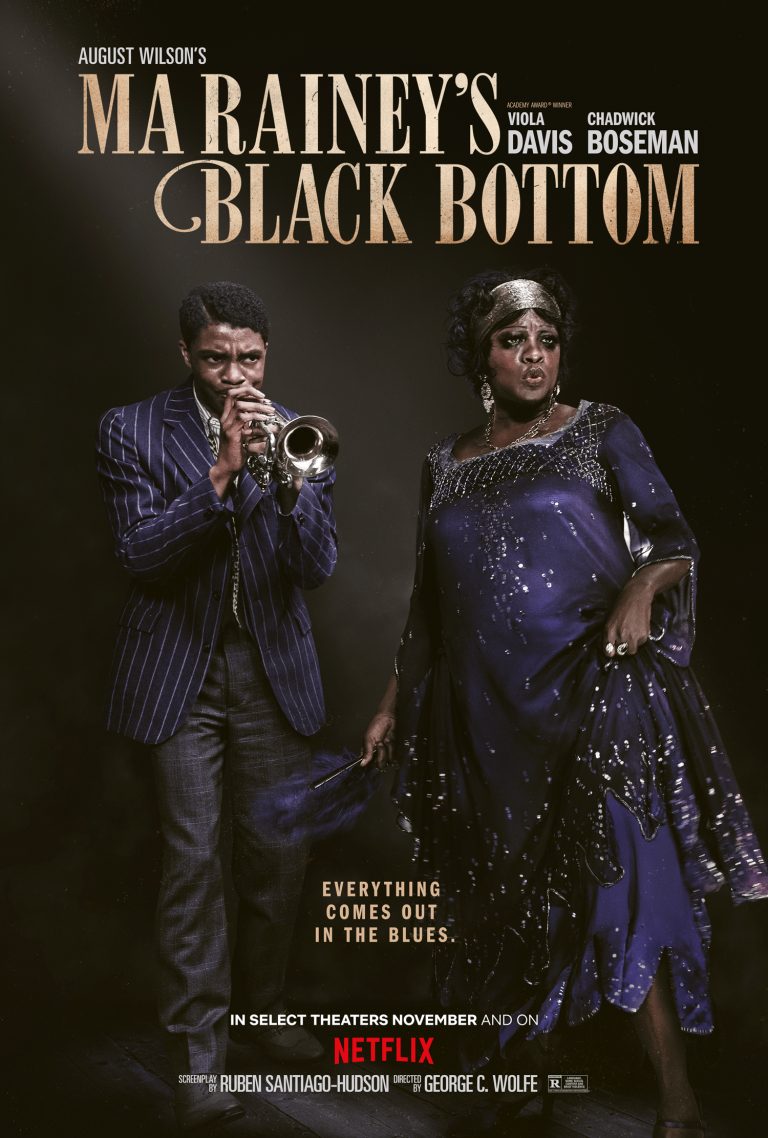

Oscar Nominations:

Leading Actor (Chadwick Boseman)

Leading Actress (Viola Davis)

Makeup and Hairstyling (Lopez-Rivera/Neal/Wilson) WINNER

Costume Design (Ann Roth) WINNER

Production Design (Ricker/O’Hara/Stoughton)

There is a difference between a movie and a play. A movie has many options for scenes and settings and, because of film editing, you can shift instantaneously from one scene to another without the story losing continuity. The camera, or multiple cameras, can circle the actors and give different views of the same scene. Sound can be layered as different tracks on the film yielding more variation in texture and feeling.

A staged play, on the other hand, is much more constrained. The audience is seated and their viewpoint of the stage does not change. Scene changes are done between different acts and usually require some kind of intermission. Actors feel a need to project their voices to make sure their sound is heard even when not directly speaking to the audience. On the other hand, a play always feels a little more intimate than a film. The actors are real flesh and blood and have just one chance to project their thoughts and feelings, not subject to multiple ‘takes’.

Movies and plays both tell stories, but they do so with different methods. And, sometimes, these different methods impact the way emotions are communicated – the feeling can be dramatically different. And so the effort to cross these mediums is often fraught with risk – things may not turn out quite the way the artists intended.

August Wilson, known as “the theater’s poet of Black America”, wrote a series of ten plays, one for each decade, documenting the black experience in America in the twentieth century. The plays, known as the “Pittsburgh Cycle” (or sometimes “The Century Cycle”), have been very well received earning Pulitzer and Tony Awards. He wrote the play, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, in 1982 and it was adapted by Ruben Santiago-Hudson for this movie’s screenplay.

Denzel Washington, another outstanding figure in the world of black culture, has chosen, as one of his pet projects, to bring to the screen all of Wilson’s ten plays. The first one, Fences (2016) earned Oscar nominations for Wilson’s screenplay, Washington’s performance, and even Best Picture. And Viola Davis won the Best Actress Oscar for her work in that movie. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is the second one in Washington’s series, and the third, The Piano Lesson, is scheduled for release next year. The Wilson/Washington partnership is on a roll.

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is a good film. Still, it is a play that has been adapted to fit the constraints, and freedoms, of a movie. And, unfortunately, sometimes the jump across mediums doesn’t work quite right. Despite the unusual amount of Oscar buzz – it ranks 7th of all 41 Oscar-nominated movies in my ‘Oscar buzz index’ – and is also seventh in the ranking of all the movies according to the Critics Metascore. But the viewing public has a different opinion, dropping it to 24th in their rankings, putting it in the bottom half!

Why the difference between critical appeal and popular excitement? Maybe because of all those things I talked about at the beginning of this essay about the differences between plays and movies! Audiences watch a movie expecting to see a ‘movie’, not a filmed ‘play’. My wife, Joan, was less than enthralled with the performances, complaining that while Boseman, for example, was sincere and honest in his performance, she felt he was ‘overacting’, trying a bit too hard to project, even ‘yelling’ his lines. What she was describing was exactly what actors in a play are trained to do – but she was observing that it doesn’t quite work in a movie! Maybe critics and people who work in both mediums are able to transcend, and overlook, the differences. But audiences should not be expected to perform that conversion – that is not what they necessarily agree to do when they sit down to watch a movie.

Having said all that, there are some terrific things about this production. Chadwick Boseman, in his last role before his untimely death, delivers what just about everyone thinks is the best performance of his career. Odie Henderson (RogerEbert.com) wrote “Underneath an exterior that’s primarily a performance is a white-hot coil of rage that scars his (Levee’s) soul the way a white man’s knife scarred his body in childhood.” Boseman’s character delivers a monologue about how God has abandoned him, as a Black man in a White world. It is one of the most passionate and emotionally draining expressions of rage that I can remember. It, no doubt, derived much of its power from his own knowledge of his impending death from colon cancer, taking him at an awfully early age of just 43. His nomination for the Leading Actor Oscar is well deserved.

His co-star, Viola Davis, earned yet another nomination for her performance as Ma Rainey. Davis has received three other Oscar nods (The Help, Doubt, and Fences) and she delivers a commanding performance here, but it relies more on stoic expressions of contempt for the white men trying to control her life, and a kind of condescension to the rest of her band. Ma Rainey runs the show and she lets everyone know it. But that’s about the extent of our knowledge of her. There is one scene where she is expressing a sexual interest in her ‘assistant’ Dussie Mae (a well done supporting role by Taylor Paige), but it doesn’t go anywhere – we’re left with a salacious appetizer and no main course!

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom did win two Oscars, for Costumes and Makeup/Hairstyling. It is interesting that these are two design arts that are shared between plays and movies, so very little is lost in the crossover. Ann Roth, winner of the Costume Oscar, has received four other nominations, all for costume design for period piece movies set in the 1950s or 1930s. Here she goes back to another decade to capture the style of the 20s, especially as worn by Blacks in Pittsburgh and Chicago. (The makeup artists are new to the Oscar game but have a range of TV and movie credits going back to films from the 90s.)

Their work, and that of the also-nominated Production Designers, produces a rich stage presence. The colors and textures of the sets, costumes, and faces are dramatic and help bring forward the spoken words, which, in a play, are the central part of the story. Ma Rainey’s heavily layered face promotes a rigid countenance befitting her powerful posture. And the constant beads of sweat promote her feelings of intensity. Although I’ve only seen Mulan and Mank as competitors in these categories, I can understand the wins.

The film was not nominated for Best Picture, unlike most of the other Oscar heavies we’ve reviewed so far. And I think we can understand the reason – this is, fundamentally, a play, not a movie. Despite a once-in-a-lifetime performance from Boseman, it is very difficult to take the intimacy of a stage play and project it onto a screen, even a home theater TV. If you step back and realize that you are really watching a play, then you can appreciate the monologues and the compacted scenes. But that requires an extra layer of effort from the viewer, something most of us are not initially prepared to do.

So, Ma Rainey is an intriguing movie, with lots of important thoughts and emotions regarding race in America, and plenty of good music. But it probably isn’t the best movie you’re going to see this year. (3 Stars)

Available on Netflix Streaming

.