Oscar Nominations:

Best Picture (Winner)

International Feature (South Korea) (Winner)

Director (Bong Joon Ho) (Winner)

Original Screenplay (Bong Joon Ho) (Winner)

Film Editing (Jinmo Yang)

Production Design (Ha-Jun Lee/Won-woo Cho)

Writer and director – and Oscar winner in both categories – Bong Joon Ho received his degree in sociology before turning to movie making. His movies reflect that background, exploring the dark side of social class distinctions in ways that people without that training may not be able to see as easily. In Snowpiercer, his 2013 movie, the message is thickly layered, almost with a trowel, as he tells the tale of a futuristic train where the lower classes live in the back of a the train and slowly move forward through stratified railway cars as they stage a bloody revolt against the ruling class occupying the front cars. The metaphor is heavy-handed and, perhaps, a little too obvious.

Six years later, in Parasite, Bong treats the same subject with a lot more nuance and creates a much more effective film. In Parasite the social classes are represented by two families, the Kims and the Parks. The Kims live in cramped quarters, half underground, in one of Seoul’s more destitute neighborhoods and attempt to make a living assembling pizza boxes and working the gig economy with mixed success. Like many in their social class, they have to deal with the miseries that poverty breeds, like living bugs and dying dreams.

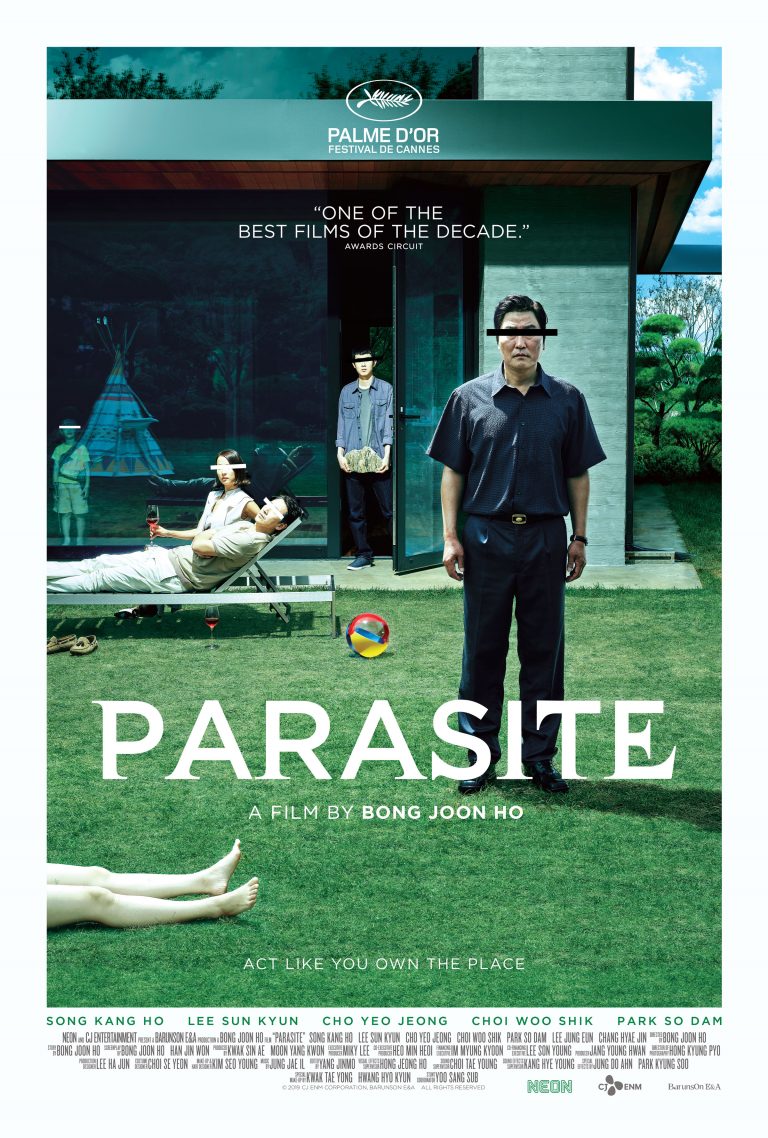

In an unusual turn of events, one of the Kims has an opportunity to tutor a child in the Park family, who occupy a distinctly higher rung on the social ladder. From there, the movie turns into a farcical con as the Kims slowly move the entire family, not just into the Parks lives, but into their house. The Park home is clearly the opposite of the Kim’s with wide open spaces, luxurious comforts, and stunningly beautiful views. The first half of the film exposes the gullibility of the Parks as they become increasingly dependent on the Kim family without really knowing just how much they have ceded. In scene after scene we see the con grow as the two families increasingly intertwine.

Much has been said about how this movie shifts between genres. And, clearly, the first half of the movie occupies the ‘comedy’ category. But then things change and the viewers’ emotions change too. Events create tension and we realize that darkness and danger are now much closer to the surface. If the first half of the movie is satirically funny, the second half becomes more like a Hitchcock thriller. But the transition isn’t immediate – Bong moves us into it slowly, which brings the tension more fully into play. The surprise is, fittingly, in the basement and you will never see it coming. But the presence grows as the movie progresses and the uncertainty of the outcome fuels the movie’s stunning climax.

Bong’s imagery is riddled with layers. Not only are both homes horizontally structured, but the transitions between them are navigated by climbing either up or down ramps, stairs, streets, and driveways. He has done a masterful job of communicating his message through cinematic staging. There is one sequence, in particular, that shows the Kim’s retreating from the Park house climbing down stairs and as the camera pulls back we see just how many steps there are and how distinctly different are their two locations. The nomination for cinematography is richly deserved.

And so is the one for editing. This is a tightly constructed film. There is some disagreement about whether the coda is fully necessary, or maybe too long. But definitely the rest of the movie moves seamlessly, conveying the viewer between each scene with perfect emotional cadence.

Much has also been written about why, even though the movie won the Oscars for Original Screenplay, Director, and Best Picture, it didn’t receive a single nomination for its actors. As the Academy increases its diversification efforts, that might well change. Some of the Korean actors also appeared in Bong’s Snowpiercer, but, like most Americans, I can’t say that I am familiar with any of them. The entire cast, of especially the Kim family, deserves special mention as does Yeo-jeong Cho who plays the Park wife and mother with an exceptional mix of gullibility and upper-class sophistication. Also pay particular attention to Park So-dam, who demonstrates a beguiling street-smart charm as the Kim daughter.

In the end, though, this is Bong’s movie and he deserves the singular credit for achieving a near-genius mastery of multiple genres. He keeps your attention by focusing on powerful issues of contemporary society. By exposing the insidious structure of class relationships spawned by unregulated capitalism, he demonstrates that much of what we identify as class struggle is really the symbiosis of our economic life. Indeed, the fundamental question behind Parasite is who is feeding off whom? And is that really the way life should be?

Although I am not sure this is really the best movie of 2019, I do agree that it ranks extremely high. A masterful cinematic experience. (5 Stars)