Oscar Nominations:

Documentary Feature

There is always at least one movie in the list of Oscar nominees that generates a lot of controversy. This year, it appears, there are at least two: “Mulan” and “Time,” the subject of this review.

Initially a co-production of the New York Times that was subsequently acquired by Amazon Studios, “Time” has become the subject of another left/right battle, this time over the explanation for the disproportionate numbers of Black and other minorities in the prison population of this country. The right seems to argue that there are so many minorities in jail because they, proportionately, commit more violent crimes. The left argues that structural, or institutional, racism disproportionately levies severe punishment on minorities, especially Blacks.

I’m not going to pretend I don’t have a left-leaning sympathies on this question, having spent many years working with the New York City Criminal Justice Agency, where I saw firsthand the bias of the criminal justice system against the less privileged in our society. Conservatives, right off the top, don’t seem to have a good explanation for why the United States incarcerates a higher proportion of its population than any other industrialized country. If America is such an “exceptional” place, why are so many of its citizens criminals? And why do people of color, especially in “red” states, suffer a higher conviction rate and receive longer prison sentences than white people who commit the same crimes?

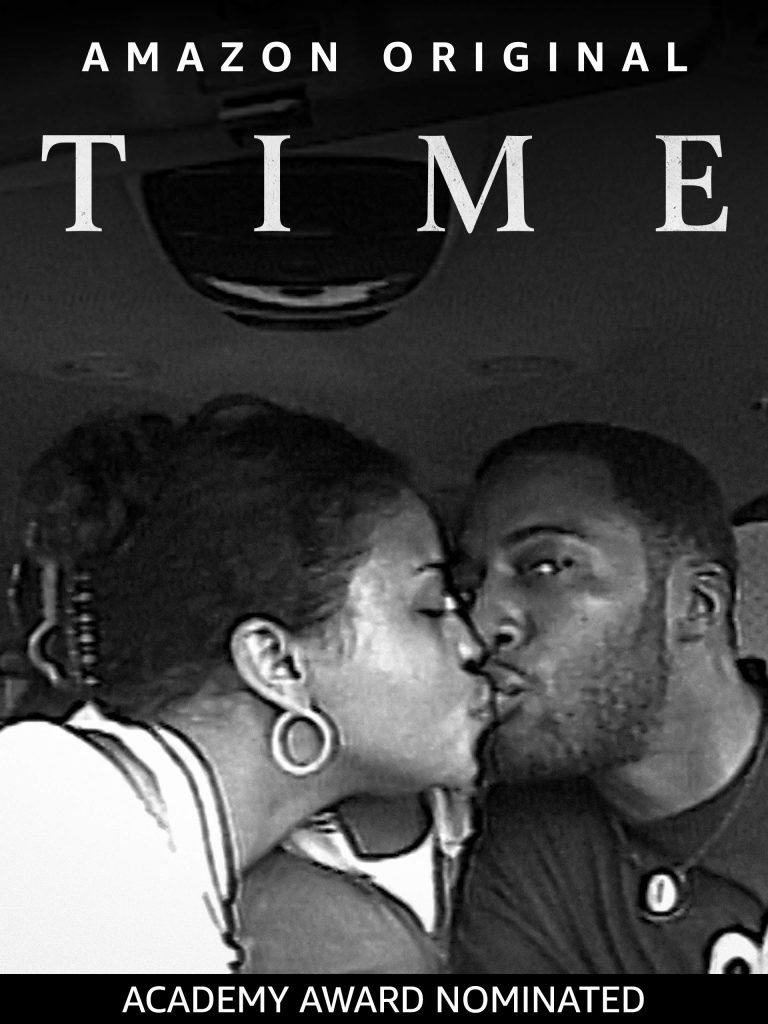

“Time” examines these questions by focusing on the experiences of one Black family, the Richardsons (Rich, for short), that falls into the criminal justice sinkhole. Two young Black people in New Orleans get married, seem happy, manage a family of six boys and, to a certain extent, prosper. They open a business selling hip-hop clothing. When the business falters, the Riches hatch a misguided plan. As the wife, mom and leading figure in the documentary, Sibil Rich, a.k.a. Fox Rich, says: “Desperate people do desperate things. It’s as simple as that.”

Robert, the husband and father, and a friend decide to rob a credit union bank and Sibil agrees to drive the getaway car. Guns are involved and the threesome are caught and prosecuted. An attorney, more interested in fees than justice, is assigned to represent Sibil, who pleads guilty and ends up with a 42-month sentence. After time served, she comes home and resumes raising her boys.

Her husband, however, apparently given different advice, ends up getting sentenced to a term of 60 years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary (better known as Angola) without any possibility for parole or probation. Sibil becomes a passionate advocate for criminal justice reform, especially in the areas of sentencing and incarceration. In her view, “our prison system is nothing more than slavery. And I see myself as an abolitionist.”

Some of the facts of the case are a little confusing. I read several scathing reviews on IMDB implying that the robbery was much more severe than depicted, with shots being fired. I also read that the Richardsons made an additional mistake during the trial of visiting jurors’ homes to plead for mercy. This could be considered jury tampering. (The documentary does not deal with either of these charges, for which I could find no confirmation. So there remains some unresolved aspects of the Richardsons’ cases that caused some reviewers to feel less sympathy for the family.

But, ultimately, I’m not sure it makes a huge difference. It still remains true that a white first offender would likely have received a minimum sentence for armed robbery, which can range from three to 20 years, not a 60-year sentence without the possibility of parole or probation. The central theme of the movie—that the U.S. penal system is racist in its application of criminal sentences—cannot be persuasively challenged.

The other important message is that a life sentences affects not only the incarcerated person, but innocent family members as well. Fortunately, in this case, Fox Rich does not crumble under the responsibility of being a sole parent and breadwinner. She manages to hold her family together while also fighting to gain her husband’s release. The subject of the documentary is, really, Fox’s amazing resilience. She not only campaigns relentlessly for 20 years, trying to bring about a new, reduced sentence for her husband. She also becomes a fierce advocate for prison system and sentencing reform. The movie paints a moving portrait of a sympathetic woman and her important cause.

“Time” was directed by Garrett Bradley, a Black documentary filmmaker best known for her New York Times Op-Docs short film, “Alone,” which won the Short Form Jury Award at Sundance in 2017. Bradley’s work on “Alone” introduced her to Fox Rich. After Rich gave Bradley more than 100 hours of home movie footage, shot over 20 years of family life, Bradley conceived the idea of making a feature-length film focusing on the Richardsons.

Much of the home movie footage, which allowed Bradley to take the “really long view” that I’ve argued in earlier reviews is a sign of a good documentary, was shot in color, but was then converted to black and white. This cinematographic choice gives the film a crisp coolness, which works well as a contrast to offset the Richardsons’ passion and warmth. For the most part, Bradley’s interlacing of the home movie footage with her contemporaneous filming is skillfully done, although there are moments when the time frame is not immediately clear. The movie bounces back and forth in the lives of the Richardson children as they grow from small boys into young men. Gratifyingly, most of them graduate from college and one becomes a doctor.

Rob Rich isn’t entirely absent. Bradley incorporates repeated shots of a life-size photograph of the father attached to cardboard cutout figure in the family’s home. The patriarch may not be there in person, but Sibil makes sure his presence is always noted. This is an example of how the Richardsons maintained their cohesion and identity.

The title of this documentary has multiple meanings, and figuring them out is one of the pleasures of watching this movie. Perhaps the most significant reference occurs near the end when many of the opening home movie frames are played in reverse—symbolizing an attempt to recapture what has been lost. The final scenes are touching, but I’m not going to spoil them for the viewer.

In the end, this is a good but imperfect movie. It attempts a sympathetic portrait of a distressed family that, relying on inner strength, manages to do fairly well. The movie mostly succeeds in conveying the Richardsons’ faith and perseverance. But nagging concerns about the honesty of the film’s portrayal of the robbery linger, perhaps unjustly. It is fair to say that, when compared to some of the other contenders in the 2020 Best Feature-Length Documentary category, “Time” doesn’t have staying power—its impact starts to fade after a day or two. Not this year’s best. (3.5 stars)