Oscar Nominations:

Documentary Feature

Attica makes you question lots of fundamentals of American society.

I have never understood why we Americans, in the “land of the free”, have the highest proportion of our population behind bars of any country in the world. Rounding out the top ten are countries like Rwanda, Turkmenistan, and El Salvador. In fact, none of the other “developed countries” come anywhere close to our rate of incarceration.

I’ve heard some apologists say it is because we are such a manifestly diverse country that violence and conflict is a necessary result, and so a strong prison system is required to maintain “law and order”. There is a problem with that argument: Based on a robust measure of ethnic and racial diversity (worldpopulationreview.com), the top ten countries in diversity, across the globe, are all located in Africa. And none of them have anywhere near the incarceration rate that we do. (Rwanda is not one of the most diverse.)

So diversity can’t possibly be the explanation, at least not by itself. But there is another factor in play in American society, related to diversity, that might actually explain more of the reason. While Americans profess to believing in the value of cultural diversity, it really isn’t clear that they profoundly believe it, deep in their hearts. Why, for example, do Black Americans make up only 13% of the US population, but are incarcerated at triple that rate?

Sure, poverty has something to do with it – poor people are less likely to be able to post bail when they get arrested and, therefore, more likely to sit in jail pre-trial, and less likely to be able to afford quality legal representation to defend against misapplications of the law. Black Americans are, statistically, more likely to be poor. And we also know that the conviction rates, and imposition of severe prison sentences, are definitely higher and more severe against Black Americans than they are for us “white folk”. But the problem with that is even when you control for socio-economic status, whites get less severe criminal penalties for the exact same crime, and it largely doesn’t matter what part of the country you are in. So there is a definite explanation for why Black Americans are over-represented in the US prison population and I’ll get back to that.

The Attica prison riot occurred in September, 1971 and it still ranks as the worst “prison riot” in US history with 29 prisoners and 10 hostages killed during the riot. I reviewed the history of prison uprisings, riots, and other violence in US institutions since 1900. There were some small disturbances before the seventies. But after Attica, there were riots resulting in maybe one or two inmates and/or guards killed in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Georgia, Ohio, California, Mississippi, Delaware, South Carolina, and Colorado. But none of them were on the scale of Attica with the single exception of the 1980 Santa Fe, NM riot in 1980. During that exceedingly-violent riot, thirty three inmates were killed. But, significantly, all deaths were caused by other inmates. A dozen officers were taken hostage and while injured and raped, none of them were killed. So Attica stands unique in American history as the prison riot where the most people died.

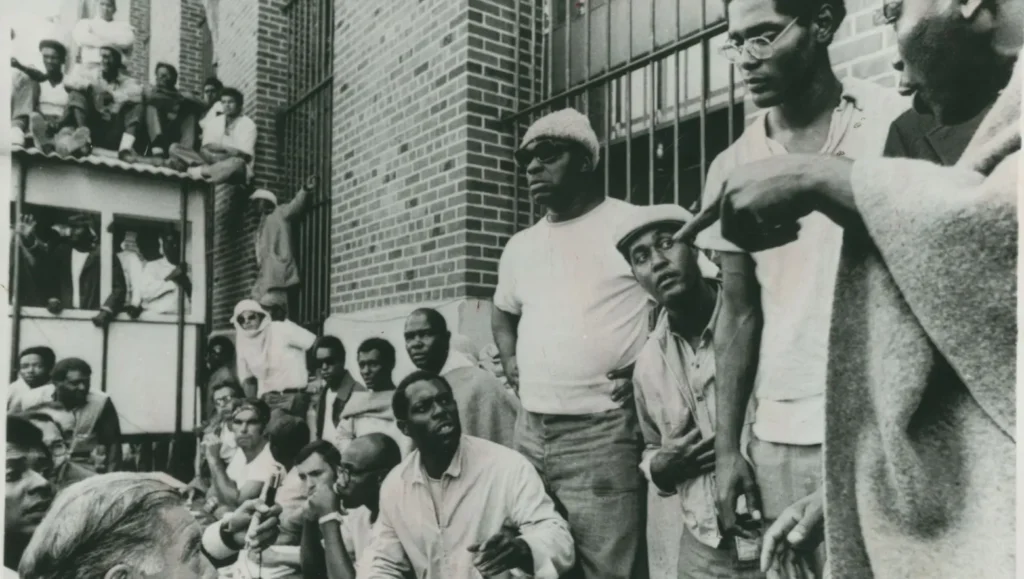

With all this information, you should now go watch this amazing documentary, the last of this year’s documentary movies see FLEE, Summer of Soul, Ascension, and Writing with Fire). The film itself is pretty standard documentary fare. It is largely the work of Stanley Nelson, an experienced Black American producing television and movie documentary films at least since the 90s. What he has accomplished with Attica is probably the final and most definitive statement of what happened there. Yes, it is a talking-heads documentary. Nelson has managed to find and interview more than a dozen people who were actually involved in the event, ranging from at least 11 former prisoners who were on the ground during the riot, to children and wives of the hostages, to a member of the National Guard brought in to provide “medical evacuation”, to members of the Observers Committee, including journalists (John Johnson) and lawyers (Alex Schwartz) who participated in the negotiations over those four days. The “heads” tell their stories with honesty and emotion – you can tell that this was not an experience they will “ever, ever,….forget”.

Nelson doesn’t settle for interviews. He also gathered remarkable archival footage. Frankly, especially in the post-riot scenes, I am surprised that cameras were allowed to film, but they did and photographers took pictures. In addition, he integrated audio recordings of Nixon talking to governor Nelson Rockefeller, both of whom played pivotal roles in determining the outcome. (Remember the famous “Nixon tapes”?). The footage, especially in the last half hour will shock you and if you are averse to vivid violence or full-frontal male nudity, then you might want to shield your eyes for the final 20 minutes – the film earns its “Mature Audience” rating. Ben Kenigsberg (New York Times) wrote that the final half-hour “…makes the case that the brutality used in ending the riot was excessive, criminal and racist – a show of force closer to revenge.” (The scenes are, quite frankly, as awful as anything you have seen coming from Nazi concentration camps – and they are not fiction.)

This is, for some reason, a very difficult movie to find. IMDB has only about three thousand viewer ratings and the Metacritic score is based on only 11 critical reviews. Showtime, who helped produce the film, is not making it easy to view it and, after trying for 30 minutes to get it from them, and spending another $12 on subscriptions (which I’m getting refunded), I ended up buying the entire film from Prime Video. And that is a real shame, because this is a film that needs wider, and easier, distribution. Especially in these times – when it seems like so little has changed in fifty years – we need more exposure to the fundamental questions of just who is an American, what does it mean to be one, and what are the minimum standards for treatment if you are, not just an American, but a human being.

There is so much more that could be written about this film and about the Attica prison riot. But I’ll leave you with just a single fact – Only one guard/hostage/officer was killed by an inmate at Attica. He was William Quinn and he died from injuries three days after a beating he suffered in an fight with inmates, just before the riot began. The circumstances surrounding that fight aren’t real clear. But it was his death that changed everything, resulting in law enforcement, not the inmates, killing more than 33 inmates and nine more of their own in a brutal assault that, if you watch the film, you will remember for a long time.

So, back to the original question – why are so many Americans, and especially Black Americans, imprisoned? If you watch “Attica” I think you end up with a pretty good answer: The US prison system is a mechanism of control and power. More specifically, it is a way that the white power structure maintains fear and loathing in a Black community that whites fundamentally want to exclude from the American dream. That might be a tough conclusion, but how else do you account for the facts surrounding black imprisonment, and the resulting Attica.

Although this is a traditionally done documentary, both its treatment and its subject are worthy of attention. (4*)

Stream on Showtime or Fubo or Buy from multiple sources (Very hard to get!)

1 thought on “Attica”

Thank you, Michael, for your customary historical research & fearless analysis.

I now want to watch this movie, though I am very sensitive to violence & may tune out the last 20 minutes.

Your work is a gift!