Oscar Nominations:

International Feature (Hong Kong)

Are critics afraid to review this film?

Simply put, I can’t find a review of Better Days by any of my go-to reviewers – nothing on ReelViews, FlickFilosopher, Sight&Sound, or even RogerEbert.com. Maybe it appears on a list of movies nominated for the International Feature Oscar, but nobody provides a review. (I read other reviews as part of my research of a film to learn more about what other people think about it as a way of fleshing out my opinions.)

Of course, the New York Times was thrown out of China because the Chinese government didn’t like the way the Times was reporting about human rights abuses and other ‘transgressions’. So maybe NYT critics refused to review this movie as a form of retribution. But, really, why is it so hard to find a review by a major-name critic? Could it have something to do with the fact that the Chinese government seems to have such a heavy-hand in everything cultural?

And, yes, there is some of that in this film. Some of it was overt in the messaging appended to the end of the film which turned a fairly good dramatic production into a political and social propaganda piece. I mean, does everything really require the stamp of the government to be acceptable? Is it not possible to trust your people to speak, think, and feel responsibly? Do you have to layer on the ‘official’ interpretation of the events like the people can’t possibly get the message on their own?

Better Days is indeed a Chinese production. Listed as from Hong Kong, it features a large number of mainland Chinese cast and crew members and was filmed largely in Chongqing, China. Mulan, the very first film I reviewed of this year’s Oscar crop, was a joint production of Chinese, US, and Canadian producers. But it too was subject to substantial criticism because it was filmed in Xinjiang, the province where Muslim Uyghurs are an ongoing problem for the Chinese regime. But this film is entirely from China and, so, we can assume, reflects a lot of the official Chinese government sensibilities – otherwise they probably wouldn’t have allowed it into the Oscar race at all.

This is the third film in the five International Feature nominees I’ve reviewed and I will be doing the remaining two next. Foreign films present interesting challenges to American viewers because there is always the undercurrent of an entirely different culture. In this case, it is not only a difference born of a radically different religious and social tradition – dating back long before western cultures can claim an origin. But also a very different political system with strong centralized control over nearly all aspects of daily life.

So, given all that, it is somewhat unexpected that the film resonates at all with western life. It is a film about the effects of bullying in secondary school and the negative impact it has on both the perpetrator and the victims. It is also about the intense pressure to succeed that, in China, is expressed in the all-important exam that students take at the end of their secondary schooling. And, finally, it is about the attraction that young people develop for each other as their hormones are exploding and they struggle to mature into, somewhat, functional adults.

Yep, sounds exactly like some typical Hollywood coming of age movie – all of those elements are what you could expect right here at home. And that is what makes Better Days attractive – that those themes are operational in China means that, maybe, they aren’t really so different than us. Yes, someone commits suicide as a result of bullying in this film – does that not happen here in the US? Yes, the exams these kids face are incredibly important, drive everything they do in their last year in school, and determine their future lives – but ask Lori Laughlin and the others involved in the 2019 college entrance exam scandal whether that pressure is unique to China. And yes, there are other, huge, events that aren’t exactly flattering to contemporary Chinese life, but which can be found in our own schools here in the US. (As I write this, we are learning the details of yet another school shooting.)

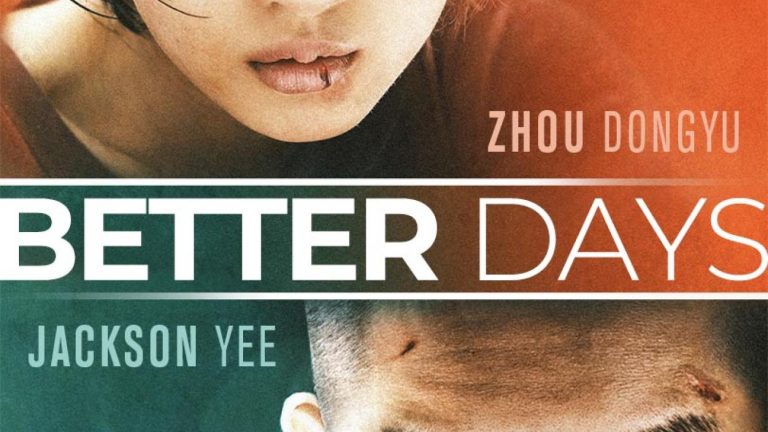

There are some wonderful things about this film. Although I am familiar with no-one on the cast or crew, I found some of the actors very convincing, especially Ye Zhou as one of the bullies and Dongyu Zhou, the young woman who plays the main character, a stoic, reserved woman who is still able to show emotions credibly through her facial expressions. The cinematography is top notch switching from wide-screen panoramas to up-close personal shots as the mood requires, and the editors did a fairly good job keeping the thing moving (although at 2 and 1/4 hours, it could have probably been shortened by 20 minutes and still retained its best elements.)

Still, though, I can’t rally a huge amount of enthusiasm for this film. My wife, Joan, really didn’t like it. And when we talked about it, it became clear that it was not only the heaviness of the themes, but also the layers of cultural differences that made her feel distant from the characters and the resulting lack of empathy. A lot of that is to be expected when we view foreign films. There is a certain amount of alienation that comes built in as we have to navigate the subtitles and the cultural differences – domestic movies are intrinsically easier to watch. But there is also a bit of Chinese heavy-handedness going on here. In ways that we don’t appreciate here in the States, the Chinese seem to have a need to make sure that everything comes with specific moral guidance. Perhaps they don’t trust their people to understand and get the message through the drama of the film and so have to layer on some directives about the dangers of bullying and how we have to combat it.

I found the film fascinating in its differences as well as how the underlying story was one that could have happened here. Some viewers, though, will find it a bit oppressive. (3.5 Stars)

Available on Hulu, Netflix DVD and to rent on Prime