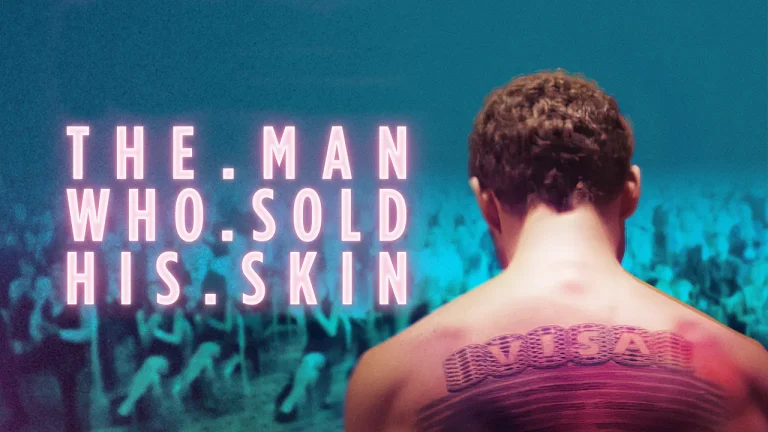

Oscar Nominations:

International Feature (Tunisia)

Recently I’ve been struggling with trying to understand the notion behind an NFT, a Non-fungible Token. An NFT is, as best as I can understand it, an entry on an electronic ledger that is, or can be, associated with some kind of digital image or file, like a photo, an audio file, or even a twitter meme. The NFT isn’t the same thing as the item it is associated with, but the NFT can then be bought and sold on an exchange network using block-chain technology – exactly like cryptocurrencies can be exchanged. So it is possible, then, if you purchase such an NFT that you, in some sense own the digital file, and the content, that it is associated with. I don’t fully get how this association and ownership chain works – just like I don’t completely understand how cryptocurrencies work. But the point is that there is a robust market for these things and they are, in fact, being traded all the time.

This film, The Man Who Sold His Skin, explores something exactly similar. Except in this case, the art work isn’t digitally stored, but instead is very real, up-front and personal. And it is also based in fact: In 2008 a Belgian artist named Wim Delvoye tattooed a artistic image on the back of a man named Tim Steiner. The ‘piece’ of art (“Tim”) was later sold to a German art collector and Tim was required to sit naked from the waist up in an art gallery for a certain number of days each year in return for his share of the payment.

Now let that bounce around your cranium a bit and try to imagine the concepts involved. The notion that people, or babies, can be bought and sold has disappeared from acceptable Western thought for decades now (although we are still navigating the residue of past practices). And we have strict laws about the sale and transfer of body parts. But what does it mean for a person to sell part of his/her body to be used as a canvas for a work of art which can then be sold to yet another party? Maybe you ‘own’ your back, but what if you’ve agreed to let an artist use it as his canvas and then the artist sells his work (which just happens to be on your back) to a collector who then has a right to enjoy that work of art in certain ways? What happens to that person’s back? In a very real sense, the man’s back has been turned into a commodity – something that, in all likelihood, will be bought and sold, over the course of the man’s life. Oh, and how do you insure such a thing? And, finally, think, just a bit, on what happens to the artwork when the man dies?

Have a headache yet? This film won’t help relieve it. All these questions will be stirred up as you watch this film, and a few more. Like, what would motivate someone to sell their back like that? The film addresses that question, although maybe not as effectively. In Sam’s case (the man with the back) we find that he is motivated by love. He desperately wants to be with a woman that, unfortunately, he cannot have. And so, his desperation becomes all the more sad because of what he is sacrificing. I thought that the love story underlying the film was well done and provides most, if not all, of the positive emotions in the film. (There is a particularly good scene on a train where Sam professes his love for Abeer, that showcases some of the excellent cinematography and acting.)

Then there is the political layer. You see, Sam isn’t just some European lost in a romantic fantasy. He is a Syrian refugee, who left his war-torn country not just to follow his love, but also to escape the chaos of his homeland. In Europe (and even more so in the US), though, he is faced with significant prejudices and biases prevalent against immigrants in general, but especially those from the Middle Eastern countries. So the film is also commenting on the way the western world is failing to adequately deal with the Syrian conflict. Look at the extremes people have to go in order to survive – even after they get out of Syria?

Ultimately, Sam finds ‘currency’ in Europe, not as a human being, but as a work of art. As a human, he is highly restrained in what he can do, but as a work of art, he can move freely all over Europe – being a commodity buys him freedom. How do you reconcile that with basic human values?

This is the first film from Tunisia to be in the International Features Oscar race. The film used recognized talent from its composer (Amin Bouhafa, who also did the music for Timbuktu) and the Cinematographer (Christopher Aoun, who did the camerawork for last year’s Capernaum). Yahya Mahayni (Sam) is actually from Syria and he does some splendid acting – I suspect we will be seeing him again. And, although this is apparently only her second film, Dea Liane did a good job as Abeer. Monica Bellucci plays a critical role, but I suspect her major contribution is simply to add a casting draw.

In the end, I thought the movie could have simply removed the political layer. There was already a good movie just exploring the complex notions of being commodified and the motivation provided by the romantic interests. I understand the attempt to amplify the plight of the Syrian refugees, but to me it felt sort of tacked on. I’m not the only one who though that. Tomris Laffly (RogerEbert.com) wrote “The machinations of Sam Ali’s crisis often feel offensively oversimplified in terms of its observations around identity and class.”

There was a good movie here that, ultimately, gets spoiled by layering on the correct, but unnecessary politics. There is already enough stuff to chew on that you don’t really need the Syrian refugee situation. For example, what would happen if someone created an NFT that was associated with the tattoo on Sam’s back? What would it mean to own that? (3.5 Stars)

Available on Hulu and to rent on Prime