Oscar Nominations:

Cinematography (Jarin Blaschke)

If you think your isolation experience has been bad, you might want to consider watching The Lighthouse. It is hard for me to imagine a situation as trying or as frightening as what these two men experience. Based on a true story, in the 1890s – of two men trapped for more than a month on a small desolate island off of New England, manning a lighthouse through a series of terrible Nor’easters – this movie paints a tale of desperation as they try and then fail to maintain their sanity.

The Lighthouse is not for everyone – in fact, no-one (except me) in our movie group much cared for it at all. It is a difficult movie to get through for many reasons and I can well understand why many people will give it a robust thumb’s down (or worse).

And yet, I was drawn to both its mesmerizing textures as well as a story that, admittedly, I kind of stumbled through. The movie received only one nomination, for Cinematography, although I think I’d argue that it should have received several more, for sound, music, and even some acting nominations. Let me start with the technical aspects before I get back to the story itself.

First, this is a black-and-white movie. It seems that every year there is at least one movie filmed entirely in black and white – last year it was the Best Picture winner Roma. More often than not, the same movie gets nominated for cinematography – there is a quality in black and white films that focuses the viewer on the faces of people and the surfaces of objects. When colors disappear, the mind pays more attention to qualities of background and foreground and the textures in play. In this case, the choice of black and white film was augmented by using a cyan filter which makes reds appear very dark. The effect on a human face is to emphasize pores and beard stubble exaggerating the coarseness of the two male subjects. Add to that an unusual choice of framing – a nearly square presentation – evoking the silent black and white films of the early 20th century. The squared aspect ratio further adds to the sense of claustrophobia and helps create the feeling that the viewer is in the dank and dark rooms with these characters.

But there is even more. Most of the movie was filmed on a spot of treeless land, Cape Forchu, jutting off the coast of Nova Scotia east of Maine. There was no lighthouse there until the film production crew built one, with auxiliary buildings that serve as the settings for most of the movie’s action. They even commissioned a lens, modeled on real lighthouse lenses, and that lens figures prominently in the movie. There are several takes where the camera eerily ascends or descends the lighthouse steps, and, from all appearances, it is a real, 1890s lighthouse.

What was not artificial, though, were the storms that ravaged the cast and crew. The actors noted that this was some of the toughest filming they have ever endured – many of the outdoor scenes were filmed in raging wind and rain, the kind of storm that makes the North Atlantic fearsome.

And with such a rainstorm might also come with fog. And with fog, a lighthouse has a foghorn. The sound design for the movie includes so many foghorn blasts, modified to resound ominously as the tension builds. Add to that a musical score that incorporates multiple unusual instruments including glass harmonicas, and a waterphone, all designed to produce a surreal background, and yet fitting for the circumstances, and the story.

I called 1917 a ‘technical marvel’, and indeed it was. But, on a fraction of the budget, The Lighthouse is nearly as good, from a technical perspective. The visual and auditory movie crafts are simply outstanding. And most viewers will, even grudgingly, concede that truth.

Where the movie may fail, for many, is in the story. This isn’t a story for the faint of heart. It is classified in the ‘Horror’ genre, and there is definitely the requisite blood and gore to make it fit there. (Remember, though, that the blood isn’t red, so…). What may surprise some people is the sexual component. There is a woman, well sort of a woman, who appears briefly (or does she) and she definitely serves a sexual function. But most of the sex is of the auto- kind. Realistically, what can you expect when two men are trapped for five weeks straight in a building that – well let’s face it, a Lighthouse has a definite shape. So what happens when two men are constrained without relief of any kind for a long time period? Especially, if neither one is particularly inclined to engage with the other?

Some might argue that the sexual component is gratuitous and didn’t need to be there. I’m not so sure. In addition to the obvious problem of two men not having any other release for an extended period of time, there is, I believe, an important reason it is in this story.

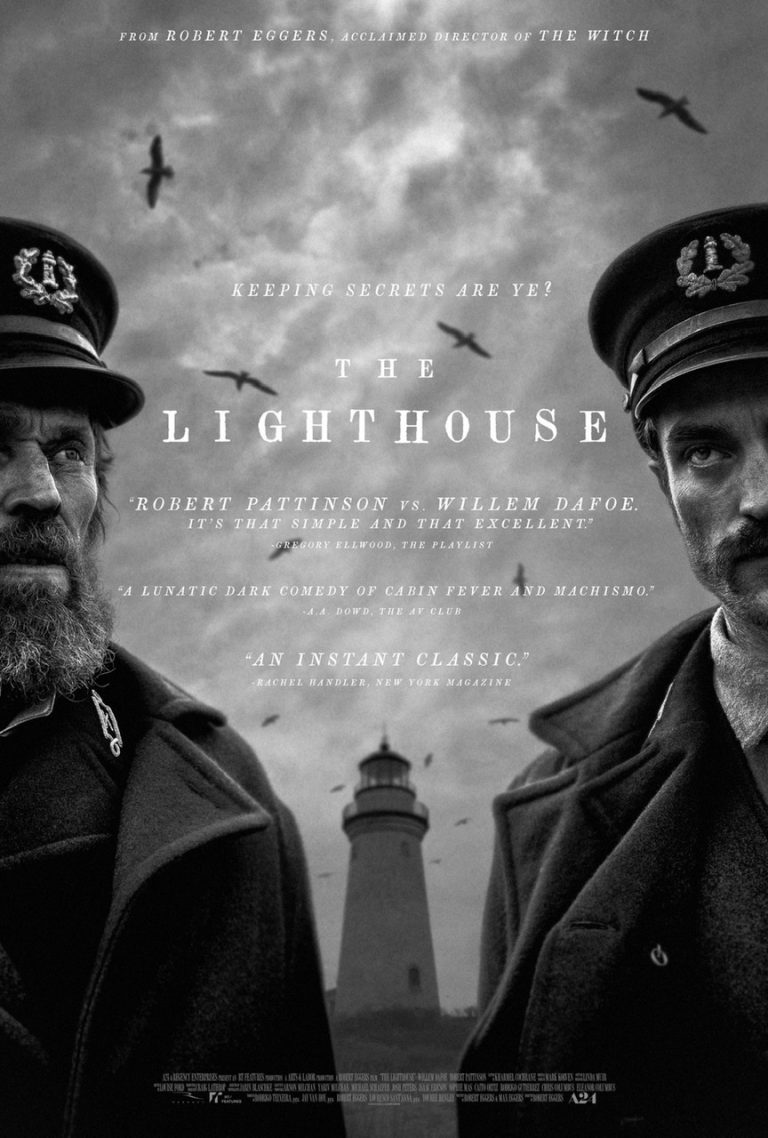

The story involves two men, played by Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson. Except for extremely brief appearances at the very beginning of the movie, those are the only two characters in the movie. (Also excepting the one woman, played by model Valeriia Karaman, who has an important, but non-speaking role). Pattinson is a young actor perhaps best known for the Twilight movies. He does yeoman’s work here in a role of Winslow that, even he reported, was among the most challenging of his career. Dafoe, on the other hand, plays Thomas Wake, the grizzled old seaman who has served at this lighthouse before and jealously guards its secrets. I didn’t like Dafoe in The Florida Project (where he received an Oscar nomination), but I thought his performance here deserving of one. So the obvious difference between these characters, and one critical to the story is their ages – one is a young man, trying to establish himself, the other an old geezer who is about spent, and knows it. I’ll come back to this in a minute.

The last ten minutes of the movie will confound most viewers – well at least it did me. I didn’t fully understand the story director Robert Eggers was trying to tell, until the very last scene which only lasts a few seconds. The movie is a new take on an old tale from Greek mythology. There are clues along the way, especially in a terrific soliloquy from Dafoe (probably the best acting I’ve seen from him) where he pronounces a sea curse on the younger man, ostensibly because the younger man didn’t like his cooking. Hidden in that speech, behind oozing drama, are the motivations for the movie. And they follow the story of Proteus and Prometheus. I’m not going to spoil the movie by going into this mythology more – I suspect it will make sense for you by the end, at least I hope it does. (I almost wonder if the very last scene should have been the opening scene!)

In the end, this is a story about aging masculinity and the challenges that young men present to older men. The sexual references are important because, as any man can tell you, sex is important to being a male. The movie is strange and, for sure, not everyone is going to like it. But there is some excellent work from two male actors, and a whole crew of talented technicians. I’m going out on a limb here, and I know it will generate disagreement, but I give this movie 4.5 stars.