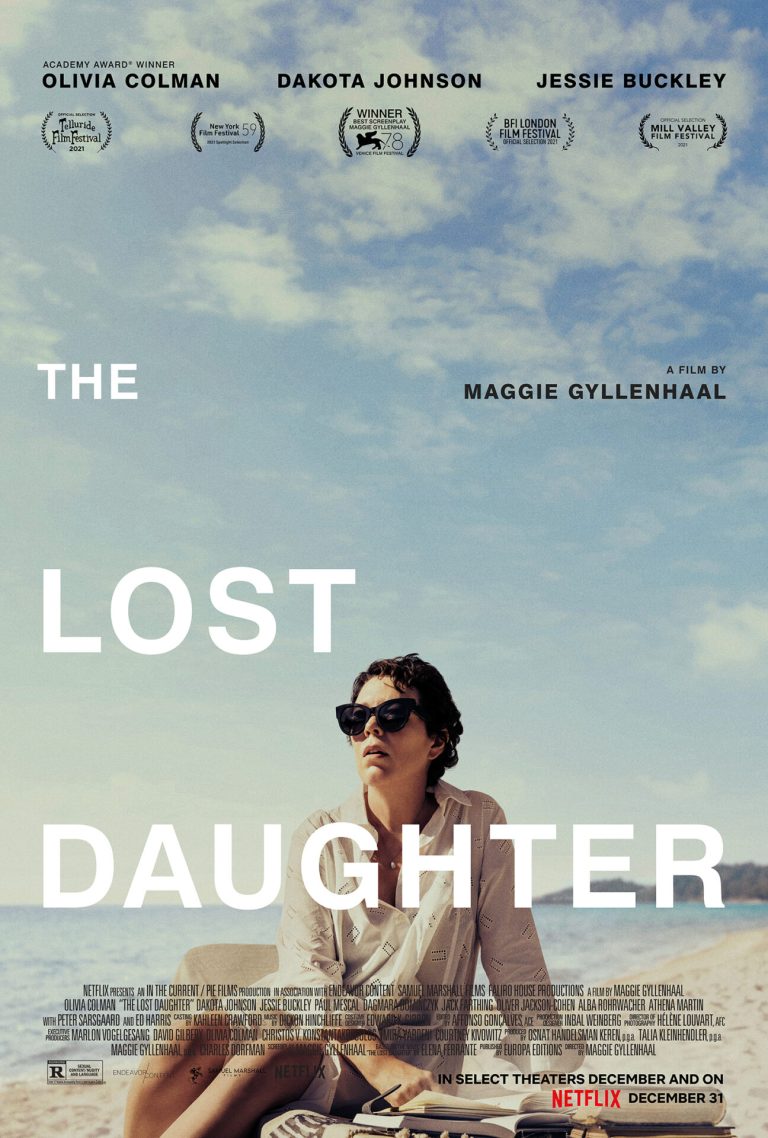

Oscar Nominations:

Adapted Screenplay (Maggie Gyllenhaal)

Leading Actress (Olivia Colman)

Supporting Actress (Jessie Buckley)

The Lost Daughter plods along at times, but is always presenting a very unique perspective on being a woman. Billed as a ‘psychological drama’, it is not a ‘psychological thriller’ although, at times, it presents forbidding notes and unexplained mysteries. The film is a complex tale of the intersecting lives of several women, but focuses on one, Leda Caruso (Olivia Colman). Colman earned an Oscar nod here for how easily she inhabits the psyche of a very complicated person.

Before I go into more depth about the ‘psychology of women’, I should perhaps make a few disclaimers. First, and foremost, I am not a woman and, therefore, I don’t think I can ever completely understand some of the threads presented in this film. (I have, however, had one Mom, three sisters, two wives, two daughters and a daughter-in-law, and a granddaughter – so I have had plenty of interaction with women – some relationships more successful than others.) But I would also argue that being male shouldn’t disqualify someone from watching this film – even for men, there is much to learn and appreciate.

Second, I haven’t read the book. The Oscar-nominated screenplay, by Maggie Gyllenhaal, is based on the book of the same name by Elena Ferrante. (Ferrante writes under that name, and has written a couple other novels that have been adapted to the big screen, but is actually an unknown – in fact, we don’t even know for sure that Ferrante is a woman, but I’m not sure that matters a whole lot). Ferrante insisted that the book could go to the big screen only if it were directed by a woman. And so Gyllenhaal (who had a terrific, Oscar-nominated performance in Crazy Hearts), also directed this film, her feature-film directorial debut. She has done a remarkable job of coaxing Oscar worthy performances from, not only Colman, but three other key women in this movie.

Olivia Colman is becoming a movie legend. A British actress, she won the Oscar for her leading performance in The Favoorite and was nominated for her supporting role in The Father. Her performance here is probably her best yet as she plays an extremely complicated woman with the right combination of assertiveness and uncertainty. Colman’s Leda is one of the most intriguing women I have ever encountered and the difficulty of the role is matched by her subtle infusion of body language signals and vocal inflections. Colman thoroughly inhabits this role.

Jessie Buckley plays the younger Leda Caruso. In what might be considered flashbacks, her scenes really work better as the all important explanations for the older Leda’s perplexing behavior – a story within a story. The young Leda is a frazzled Mom who loves her children, but is also very much involved in the intellectual work of a being a graduate student in comparative literature. Trying to balance the incisive demands of motherhood and the more-immediately rewarding life of an academic, she eventually reaches a heart-breaking decision that changes her personal dynamic for the rest of her life. Buckley’s performance is outstanding and I think she should have won the Oscar for this performance. (Buckley first reached my attention as Judy Garland’s assistant in Rene Zellweger’s Judy, and I said then that we would be seeing more of her.).

Buckley and Colman never appear together in any scene – they can’t, as the same woman at two different times in her life. But there is a curious resemblance between the two faces and Buckley’s performance foretells perfectly Colman’s impersonation. I have to believe that the two actors had lots of conversations about how to create a single persona – they even share some of the facial expressions, the turn of the mouth, and the wrinkle of an eye. Although Buckley was Oscar-nominated in the supporting role, her performance is at least as important as Colman’s.

Gyllenhaal draws even more superb performances from two more women, Dakota Johnson and Polish actress Dagmara Dominczyk. Johnson, besides being the sexy beauty in Fifty Shades of Grey, here plays a young mother, Nina, who, though she loves her young daughter, is also very exhausted. We never quite understand Nina, but we know that she, too, is frustrated. As Leda observes Nina, memories of her younger self flood in and she is forced to relive a very important time in her life. Dominczyk, as Callie, plays a relatively minor role, but has several interactions with Leda that reinforce the confusion Leda faces.

There are men in the film and the older Leda interacts with them in often rather strange ways. Lyle (Ed Harris), is the caretaker of the apartment Leda rents in Greece and tries to get Leda sexually interested, but she, not knowing what she wants, both encourages and then rebuffs his advances. And she has an intriguing conversation with Will, a college student, where she openly discusses her breast size, but then isn’t interested in him either. Men seem drawn to Leda and then find her impenetrable – in so many ways.

One technical quality that makes this movie remarkable is the emphasis on close-up photography. The camera is, literally, in the face of these actors observing carefully their conversations, the way the mouths close and open, the darting of the eyes – we learn so much. Watch, for example, how Lyle describes his own relationship with his children – you learn much even with little spoken.

But back to Leda – what makes Leda so strange? That is probably the central question in this film, and its answer is both obvious and unknowable. Early in the film Leda makes a crucial statement to Callie, just before wishing her a Happy Birthday. Callie is well along in her pregnancy and, after some banter about birthday cake, Leda pointedly says that “Children are a crushing responsibility.” The careful choice of that adjective is critical to understanding this film.

The title of the movie is intentionally ambiguous. Try to identify exactly who is “The Lost Daughter”. And maybe that is part of the point of the film. The practice of motherhood is often simply assumed to be part and parcel of being a woman. But what if it isn’t any more an essential part of being female than it is for a man? Maybe being a mother isn’t something ‘natural’ for all woman and maybe, and rightfully, not all women should be Mothers. And maybe that is what ultimately causes a daughter to be lost – as Leda puts it, ‘I am an unnatural mother.’

I loved most of this film and how it helped me put myself more into the mindset of a certain kind of woman. (I am, at this time, having serious problems with my own ‘Lost Daughter’.) But this isn’t a perfect film. I don’t know how the book ends, but I found the ending of the movie particularly unsatisfying. It isn’t that I require neat and tidy endings. But in this case, I really don’t know exactly what we are supposed to think or feel. I sense that either Ferrante, or Gyllenhaal, got a little lazy with the end and didn’t take a position on how this all worked out for Leda, or for themselves. And I don’t agree that being ambiguous is an acceptable resolution.

For that reason, I can only give it 3.5 stars.

Available on Netflix Streaming

1 thought on “The Lost Daughter”

I saw an interview with Maggie Gyllenhaal about this film, I think it was on CBS Sunday Morning. It sounds indeed intriguing, lots of questions…