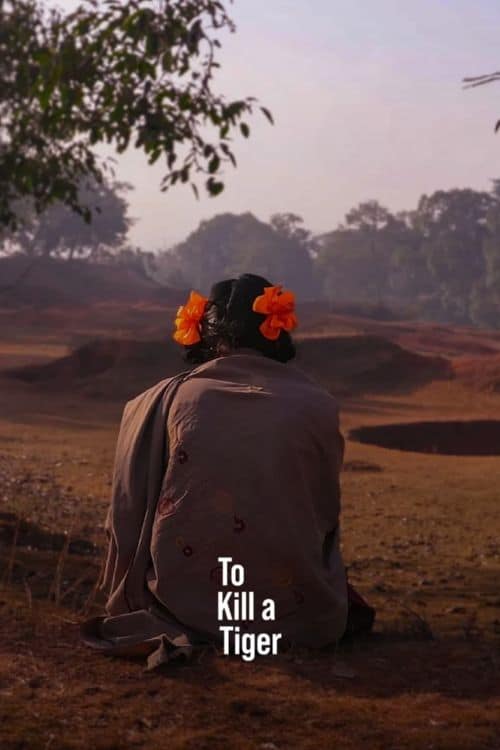

To Kill A Tiger – Snapshot

To Kill A Tiger is a film about a 13-year old girl who is brutally gang-raped in rural India but refuses to yield to social custom. Instead, with the help of her loving father, she seeks justice. In the process she may very well contribute to significant social change. (4*)

Where to Watch:

Stream:Netflix

Rent: (Nowhere)

To Kill A Tiger – The Oscar Buzz

Oscar Nominations (1) / Oscar Wins (0) :

Documentary Feature

To Kill A Tiger is an Indian movie largely backed by Canada. With 27 people credited as “Producers”, many of them from outside of India, the movie is an international production. Dev Patel is one of the producers and he was the main star of Slumdog Millionaire, which won 8 Oscars. The cinematographer, Mrinal Desai, manned the camera in that film , as well as this one. None of the other key people in this film’s development , including the young director, Nisha Pahuja, have any prior Oscar involvement nor could I identify any overlaps with other films that I’ve seen. In short, there is little Oscar Buzz about this movie. It has also not been widely released and only this year has Netflix picked it up for streaming.

To Kill A Tiger – Related Movies

Slumdog Millionaire: (Some of the Producers, Cinematography)

To Kill A Tiger – What Others Think

As a result of its limited release history, not many people have rated To Kill a Tiger, with one of my rankings based on less than 2500 ratings. So it probably isn’t too surprising, nor meaningful, that audiences place this film solidly in the middle of the five documentaries. Viewer comments included “Disturbing, but riveting” and “revolting, deeply painful.” But, largely because viewers who rate documentaries tend to be enthusiastic, the movie ranks tenth out of all 38 films, tied with Perfect Days and Anatomy of a Fall.

To Kill a Tiger hasn’t received a lot of professional reviews either, with the Metascore aggregate based on only five reviews. However, those reviews are so enthusiastic that they end up placing the movie first out of all five of this year’s documentaries and second out of all 38 movies, tied with The Boy and the Heron and just behind Perfect Days. Critics found the documentary highly emotional. Peter Sobczynski (RogerEbert) called some of the scenes “… devastating and anger-inducing…” He also alludes that it is “so intense at times it might prove to be too much for some.” Still, he notes that To Kill a Tiger is not an especially artful example of the documentary form.” Devika Girish (New York Times) gave it a Critics Pick and said it was “bristling with…invigorating defiance.”

Clearly the film provokes emotions and many people found it important that way. Averaging all the available ratings, the movie ranks second in the documentary category, behind 20 Days in Mariupol, and fourth out of all 38 films, tied with the Best Picture winner, Oppenheimer! Based on the ratings, this is a very successful movie that people need to see.

To Kill A Tiger – Special Mention

Rape in India – To Kill A Tiger is a story of a gang rape of a thirteen year old girl in a rural village in India. Rape of any kind is morally indefensible but it becomes especially ugly when it involves a young child. I tried to find information to put this event in context and, of course, it isn’t real easy to get accurate data. If you look at reported crimes, the incidence of rape in India is lower than in the U.S. and other countries including France, Russia, Italy, and Brazil. And only 10% of reported rapes involve minor children.

But, as To Kill A Tiger makes abundantly clear, the problem in India is all the cultural pressures to not report a rape especially if it involves minors. Coming up with how much underreporting is actually occurring is difficult to assess. The film suggests, at the beginning, that a rape occurs every 20 minutes in India, but exactly how many of them are child rapes is nearly impossible to determine. Human Rights Watch estimates that a rape of a minor occurs at a rate of 1.6/100,000 people. And another study on sex trafficking and sex crimes against minors ranks India as seventh worst out of all nations studied.

We can assume, though, that the child rape issue is likely much worse than suggested in the official statistics. The message of To Kill a Tiger, though, is maybe that’s about to change.

To Kill A Tiger – Michael’s Moments

To Kill A Tiger, unlike last week’s film Four Daughters, is a true “talking heads” documentary. There are no re-enactments and no professional actors in this film. Intermixed with some beautiful landscape scenes of rural India, the “action” is exclusively people talking and feeling about what has happened and what may yet occur.

The story revolves around two people, a thirteen year-old girl who goes by the name Kiran in the movie (to protect her privacy), and her father, Ranjit. He is a rice farmer and they live in a small rural village in India. Early on we hear Kiran tell the story of how she was brutally gang-raped and beaten after attending a local wedding. Locked in to centuries of local customs, crimes like this are almost always handled “locally” and usually involve the girl marrying her rapist, rather than even report the crime, and by doing so she removes “the stain on her character.”

What makes this event different is that Kiran has no intention of marrying one of the boys and, because of her strength, her father, Ranjit, supports her. The filming starts after the crime has been “investigated” by local authorities and, instead of yielding to village custom, Ranjit files an official report and the case goes to trial. They are supported by a regional social justice foundation, the Srijan Foundation, and an independent film crew assembles to document what happens.

What To Kill A Tiger documents are both the courage and conviction of the daughter and father, but also the strength of cultural tradition and how the maintenance of social behavior is strongly regulated by the enforcement of norms and customs. It also gives insight into how such norms and customs can be changed, although it involves enormous work and no small amount of risk.

The strength of this documentary is in how fluidly it simply documents the conversations, feelings, and facial expressions of the key players as these events unfold. I didn’t see any attempt at editorializing and I don’t even remember a narrator (there are some factual printed statements at the beginning and end), but the movie tells this powerful story entirely by the strength of its camera work and the skillful editing. At a little over two hours long, it could have been slightly shorter without sacrificing effect, but the viewer is presented with such powerful statements and honest opinions that you feel like you are a witness to these amazing events. It is also true, as pointed out by several viewer comments, that the film will make you angry, not at the filmmakers, but at some of the people opposing the courageous family. It also, though, makes you feel pride that for a couple of hours, you got to know something about these two people. That is the strength of the film and the reason to see it.

To Kill A Tiger reminds me of two other documentaries for very different reasons. The first is Writing With Fire which tells the story, also in India, of forty women, all members of the Dalit, or untouchable caste, who, using little more than their cell phones, create and publish a newspaper focusing on the injustices and abuses that their region absorbs as a result of behaviors from those above them, which is just about everyone. Like this one, that movie tells a story of women making significant changes in the Indian social system with courage and conviction, as well as some serious setbacks. These women, like Kiran, show that it might just be the women of India who engineer real social change.

Unfortunately, the other comparison is not a favorable one. To Kill A Tiger takes a very deliberate documentary approach to their subject matter and fills it with lots of talking heads. What makes the film so unusual and work so well is how intimate they managed to get with their two main subjects. This is a testament to the film crews dogged determination to follow the story wherever it might go.

In that exact manner it is very similar to Free Solo, the acclaimed movie that documented Alex Honnold’s free (i.e. no rope) climb up the sheer face of El Capitan in Yosemite. The filmmakers didn’t exercise any real creative judgments in either movie – they simply followed their subjects. The emotions derived from the movie are not the work of the filmmakers but come from the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of their subjects. In both cases, the films are riveting and produce strong, but very different, emotional responses. But do the filmmakers deserve the credit? In my review of Free Solo, I argued that while there was some mountain climbing skills involved in filming that movie, it was Alex Honnold who climbed it without ropes and took the risks. So I took some exception that the film won Best Documentary when the major decision of the filmmakers was simply to turn the camera on. To me “Free Solo is a compelling movie that everyone should see. But it was too easy to make for the filmmakers to receive an Oscar.”

I have similar feelings about this one, although I definitely concede that To Kill a Tiger involved more work. I’ve struggled for years to define what makes a good documentary and don’t seem to get any closer. This movie is a powerful film that anyone interested in the plight of women or social change should definitely see. Is it a “good documentary”? I guess I’m still not sure. (4*)