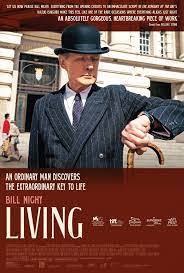

Living – Snapshot

Living is a remake of a 70-year-old Japanese film with the setting changed to London. The story is a classic, about a man who, told he only has six months to live, suddenly decides to do something different with his life. Nighy’s acting is “spot on”, and the film is a tearjerker, but ultimately it doesn’t present anything new.

Where to Watch:

Stream: Netflix

Rent: Prime/Apple/Google/Vudu/YouTube (all $5) or wherever you get your disks

Living – The Oscar Buzz

Oscar Nominations:

Adapted Screenplay (Kazuo Ishiguro)

Leading Actor (Bill Nighy)

Living did not win an Oscar, but it was nominated in two major categories, for the adapted screenplay and the leading actor. The screenwriter, Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Japan but his family moved to London in 1960, when he was only six years old. He won the Nobel prize in Literature in 2017. Noting the similarities between British and Japanese national character (see below), he had always wanted to adapt Kurusawa’s 1952 film Ikiru to a British setting from its original Japanese roots. From the beginning of his project, he had always imagined Bill Nighy playing the central character.

Bill Nighy plays Mr. Williams, the main character who received his first Oscar nomination for this performance. Born in 1949 in Surrey, England, he won the BAFTA Supporting Actor award in 2003 for his role in Love Actually. He has starred as an un-dead character in two Underworld films, two Pirates of the Caribbean movies, and in Shaun of the Dead, making his nickname in this film “Mr. Zombie” a rather pointed reference. You can notice a disability in his hands, known as Dupuyten’s Contracture, where his ring and small fingers are permanently curled inward, a condition that may give him a special insight into life’s sufferings.

With two major nominations, Living earns a rating of four on my Oscar Quality Index, placing it 13th, or exactly in the middle, of the 25 general interest films in this year’s Oscar slate.

Living – The Movie’s Family Tree

The Following Movies Share Talent with This One

(and if you like these films, you might like this one):

Ikiru (52) : (Living is a remake of this Japanese classic, somewhat modernized and set in and around London, England. More about Ikiru in the special mention section.)

Moffie (19)/Beauty (11)/Shirley Adams (09): Director (Hermanus); Cinematographer (Ramsay)

The Young Victoria (09)/The FavouriteThe Favourite (18)/The Irishman (19); Mary Poppins Returns (18)/Carol (15)/The Aviator (04)/Shakespeare in Love (98): Costumes (Powell)

It isn’t surprising that a director brings along people who have worked with him before. In this case, the most prominent retaining member of his team is the Cinematographer, Jamie Ramsay. Ramsay incorporated a novel idea in this movie by filming it in the unusual aspect ratio of 1.48:1, which seems especially good for portrait images, of which there are many. Since the movie was set several decades ago in a London that was even more “British” than it is now, the costumes are part of the charm of this film. So if you like other work by Sandy Powell – some listed above – you will enjoy her work here.

Bill Nighy is a known British actor, having played numerous roles. In addition to his Mr. Zombie characters (see above), his performance in Love Actually was appropriately recognized.

Living – What Others Think

Living didn’t score real well with the viewing public, placing 17th in my two audience rating scales. Viewer comments frequently mentioned that the original Japanese movie was better and that, despite a great performance by Bill Nighy, the film was very slow moving and somewhat manipulative.

Critics, on the other hand, were a little inconsistent, but, on average, placed this movie 7th out of the 25 general interest films. Brian Tallerico (RogerEbert) called the film “A moving elegy on the value of life…” and that the update was successful “…because of the attention to detail and emotional current of the people who made it.” Matt Zoller Seitz (RogerEbert) noted that “…it’s a little too subdued at times and has a tendency to fixate on Williams’ mostly unarticulated sadness – but it’s consistently involving.” James Berardinelli (ReelViews) argues that it “offers restrained optimism leavened with enough cynicism to win over those who might be less enamored of something more artificial.” He calls it one of the year’s best films. And the New York Time’s Beatrice Loayza liked the film, but found that it “wallows generically, employing an overbearing piano score as the camera repeatedly sits with William’s sadness to diminishing effect.”

In my combined audience and critic scale, Living ranked ninth, tied with All Quiet on the Western Front and The Fabelmans.

Living – Special Mention

Ikiru – The word Ikiru means “to live” in Japanese and this 1952 film, directed by Akita Kurosawa and written by Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni was one of the early classics from the Japanese film industry. Ikiru is ranked #97 in IMDB’s Top 250 Movies of all Time. I remember viewing the film five decades ago in one of my college Wednesday night movie screenings and remarking on how simple, but effective the story was. The film was, supposedly based on the 1886 work The Death of Ivan Ilyich by the Russian Leo Tolstoy. Perhaps, then, the basic theme of coming to a late understanding of the meaning and value of life, is a cross-cultural theme – not sure that’s a surprise, though.

Kurosawa was one of Japan’s leading filmmakers responsible for several important movies including The Seven Samurai (54), Ran (85), and Kagemusha (80). He received a Best Director nomination for Ran in 1985.

Japan and Great Britain – Since Ishiguro, the writer of Living, had long wanted to write a version of Ikiru but set in Britain and he was born in Japan but then moved to Britain, I was curious why he was enthralled by the prospect. I mean, why was a British setting more appropriate than say having the story set in, say France, or Mexico?

Although occupying nearly opposite positions on the globe, there are a lot of similarities between Japan and Britain. They are both islands located in temperate zones and sharing similar, but not identical, ecological biomes. Because of their island settings, they were, historically, more defensible, had many ports, naval access, and strong militaries – in fact their historical trajectories are similar with long histories dominated by monarchies, established military traditions, early industrialization, and very active participation in global trade.

Perhaps because of these geographical and historical similarities, there are distinct similarities in their national character and culture. There are obvious behavioral traits like driving on the left side of the road, drinking tea, and enjoying gardening. But there are also similarities in national personality that seem reflected in similar values of propriety, modesty, attention to duty, self-restraint, and control of the self. Perhaps it is these similarities that drove Ishiguro to adapt Ikiru to a British version, Living.

Living – Michael’s Moments

I was looking forward to this movie, but after the first viewing, I felt somewhat disappointed. The film is indeed slow moving but, thankfully, isn’t overlong. And Bill Nighy gives what is probably the best performance of his career. But the film felt too transparent, and obvious – everything just sort of fell into place too neatly. Like many other viewers, I cried towards the end, but after thinking about it, I felt somewhat manipulated.

My wife, Joan, had similar feelings, having given it just a C+. But, she said, the best part of the movie was the last thirty minutes. And she wondered what would happen if the director had inverted the sequencing, so that the last thirty minutes came first and, leaving lots of unanswered questions with the rest of the film filling in the gaps.

So, not having anything better to do with this film, I, for a change, listened to my wife. On my second viewing, I started the movie at scene 12 on the DVD version (approximately 65 minutes in). It resulted in a more challenging experience and, if you haven’t seen the film yet, you might consider making this programming change. (Note: if it had originally been done this way, there are certain changes in the script and editing that would have to have been done, but I think you get the gist of the experience anyway.)

The first fifteen minutes of the movie (as intended by the director) is the setup. We are introduced to all the major players and, especially, to Mr. Williams’ life which is so mundane and repetitive that you have to think he is, indeed, “Mr. Zombie”. He isn’t living – he is just existing.

Around 17 minutes, things change dramatically. Mr. Williams learns that he has cancer and can only expect to live another six to nine months. Watch his facial expressions as he comes to understand what he has been told. (In fact, pay close attention to his face whenever he is on the screen – Nighy does most of his emotional expression through his eyes and the way he holds his face!)

The next twenty minutes do not take place in London, but are somewhere else. In point of fact, I don’t think it matters – it is important that it be “somewhere else”. Mr. Williams attempts to let go, but in ways that are so foreign to him that he ends up feeling even worse than before. It is an interesting and necessary experiment, but it fails.

At the 38 minute mark, Nighy begins a relationship with someone who, sort-of-used-to, work for him. I say “relationship”, but it really isn’t romantic – it is an old man discovering what he has missed. The relationship continues for a few days (or nearly 30 minutes in the movie) and is the self-discovery part of Mr. Williams journey.

The key insight occurs as he reminisces about his childhood at the 1 hour and 4 minute mark. (If you invert the movie as I suggested at the beginning, I think it is important that you not start the film before this point). But once Mr. Williams understands what his life means to him, then the rest of the film is how he turns meaning into action.

The idea that we don’t really appreciate life until our mortality is looking us in the face is not a new one. Some people get it earlier and some never do. But for most of us it takes a series of jolts to move us into a different trajectory – one more consistent with having some purpose and meaning in our lives.

The film isn’t the best and I agree that it is manipulative and somewhat simple-minded. (And I really didn’t like the totally cynical insert near the end back at the office, for example.) But for no other reason, watch it for Nighy’s performance and for a reminder that life is short and you need to live it to the fullest while you have it. (3*)